How Much Precision Do We Need? Quantifying HDC-on-CiM Noise Tolerance and Energy Savings¶

Abstract¶

Compute-in-Memory (CiM) and Hyperdimensional Computing (HDC) offer complementary paths toward energy-efficient machine learning. CiM minimizes data movement by performing analog vector-matrix multiplications in situ, while HDC provides algorithmic robustness under low precision and noise. This paper quantifies how far CiM precision can be reduced for HDC classifiers before accuracy breaks down, and what energy savings this enables. We build a compact HDC-on-CiM simulator that injects additive and multiplicative analog noise and emulates analog-to-digital converter (ADC) quantization using a train-learned global scale (fit once at 8 bits, then evaluated at 3-8 bits) and per-dimension quantization, averaging over multiple model initializations and noise draws to obtain smooth, comparable accuracy-noise-energy curves. On the 10-class MNIST benchmark, a lightweight gradient-trained HDC classifier maintains remarkably stable accuracy across both noise and precision: under additive Gaussian noise up to \(\sigma = 0.20\), accuracies for 3–8 ADC bits remain within roughly \(0.4\) percentage points of the 8-bit baseline, with multiplicative noise causing an even smaller deviation. In an ADC-dominated energy regime, reducing precision from 8 to 4–5 bits lowers modeled per-inference energy by approximately \(50–55\%\) while preserving accuracy within this narrow band. These results identify practical precision–energy operating points for CiM–HDC co-design and illustrate how algorithmic robustness can be directly traded for circuit-level energy savings.

Additional Key Words and Phrases¶

Compute-in-Memory (CiM), Analog In-Memory Computing (AIMC), Hyperdimensional Computing (HDC), Learned Distributed Codes (LDC), Gradient-Based Training, ADC Quantization, Quantization Noise, Noise Tolerance, Precision Scaling, Energy–Accuracy Trade-off, MNIST.

Introduction¶

AI’s computational appetite is rising quickly, and energy is the constraint that increasingly matters. Much of the cost comes from moving data rather than arithmetic itself: the von Neumann bottleneck makes shuttling activations and weights between memory and compute the dominant energy budget in many workloads.

Compute-in-Memory (CiM) architectures attack this bottleneck by performing analog multiply–accumulate (MAC) operations inside memory arrays, reporting large, sometimes order-of-magnitude energy gains compared to conventional digital accelerators in prototype systems123. However, real devices bring non-idealities such as thermal noise, IR-drop, and device variation, and the energy and latency overheads of converters (ADC/DAC) can erode headline gains—particularly as precision increases4.

Hyperdimensional Computing (HDC)—also called Vector Symbolic Architectures (VSA)—offers a complementary algorithmic lever. It encodes information in high-dimensional vectors and relies on simple arithmetic operations such as binding, bundling, and permutation. These high-dimensional embeddings are intrinsically robust to quantization and stochastic perturbations, and they map naturally to vector–matrix products that CiM hardware computes efficiently56.

Prior work has advanced both fronts: programmable CiM fabrics and converter-aware architectures on the hardware side1243, and demonstrations that both classical and learned hyperdimensional representations maintain accuracy under low precision and noise on the algorithmic side5678. What remains under-specified is the quantitative map from CiM-style precision and noise to end-to-end accuracy and energy for HDC workloads (including lightweight gradient-trained variants), particularly on standard benchmarks such as MNIST. Existing studies often rely on single seeds or uncalibrated quantization models, leaving a gap in reproducible, smooth accuracy–noise–precision curves that can guide hardware–algorithm co-design.

This paper makes three contributions. First, we develop a compact HDC-on-CiM simulator with calibrated quantization, lightweight gradient-based training, and parametric energy modeling. Second, we systematically evaluate accuracy–noise–precision trade-offs on MNIST using multiple model initializations and noise draws to obtain smooth, reproducible curves. Third, we derive a quantified mapping from ADC bit-depth to energy savings that identifies practical precision operating points for CiM–HDC co-design.

Problem Statement¶

The goal of this project is to quantify how CiM analog noise and ADC bit-depth affect the accuracy of an HDC-style classifier (including lightweight gradient-trained variants) and the corresponding energy per inference, in order to identify practical precision–energy operating points. In other words, we aim to establish how much analog noise and quantization such classifiers can tolerate when executed on CiM hardware, and what energy savings these tolerances enable, particularly on standard benchmarks such as MNIST.

This question matters because converter energy often dominates system power at higher precisions. Being able to operate reliably at lower bit-depths directly translates to reduced energy consumption and potentially higher throughput. Determining the quantitative tolerance of hyperdimensional models to analog noise and quantization thus enables concrete design rules—such as the minimum ADC precision that preserves baseline accuracy—and informs compiler and runtime policies for adaptive precision scheduling or shared converter allocation.

Answering this question provides three immediate benefits. First, it yields empirical precision guidelines for deploying HDC-style models on CiM hardware, based on smooth and reproducible accuracy–noise–precision curves obtained through multiple initializations and noise draws. Second, it supports dynamic control of energy–accuracy trade-offs by adjusting ADC precision in response to workload requirements. Finally, it establishes a reproducible baseline for extending the model to more detailed physical phenomena such as IR-drop correlations, temporal drift, and device variability.

Technical Approach¶

To explore the quantitative relationship between analog noise, ADC precision, and classification accuracy in HDC-style systems, we developed a compact and transparent HDC-on-CiM simulator. The simulator models three key aspects of a CiM system: (1) the encoding and inference process of an HDC-style classifier (including lightweight gradient-trained variants), (2) the effect of analog non-idealities such as additive and multiplicative noise and limited converter precision, and (3) the corresponding energy cost per inference. Each component is intentionally simplified to isolate the most salient interactions between algorithmic robustness and hardware constraints, providing a reproducible baseline for future analog-aware co-design studies.

HDC Encoding and Inference Model¶

Our simulator employs a lightweight, gradient-trained variant of hyperdimensional classification inspired by learned distributed codes (LDC)8. Rather than relying on randomly generated hypervectors and prototype bundling, the model learns both a high-dimensional projection and a set of class vectors through stochastic gradient descent, yielding higher baseline accuracy while preserving the robustness characteristics associated with distributed representations.

Each input feature vector \(x \in \mathbb{R}^{F}\) is mapped to a \(D\)-dimensional embedding through a learned projection matrix \(W \in \mathbb{R}^{D \times F}\):

This real-valued \(D\)-dimensional embedding functions as a hyperdimensional representation and classification decisions are made via inner-product comparisons in this space.

The classifier maintains a learnable matrix of class vectors \(H \in \mathbb{R}^{C \times D}\), with one row \(H_c\) per class. Given the embedding \(z(x)\), the classifier computes logits

followed by a softmax and cross-entropy loss during training. Both \(W\) and \(H\) are updated using manual gradient descent with \(\ell_2\) regularization (weight decay). At inference time, the predicted label is

This formulation retains the computational structure that maps naturally onto analog in-memory computing: both the projection \(z(x) = W x\) and the similarity scores \(s_c(x) = H_c \cdot z(x)\) consist of vector–matrix multiply–accumulate (MAC) operations that CiM arrays implement efficiently. In our simulator, noise and quantization are injected at the MAC-output level, reflecting the values a CiM core would expose before digitization.

Modeling Noise and Quantization¶

To emulate CiM non-idealities, the simulator injects controlled amounts of analog noise at the MAC-output stage. Given a real-valued MAC output \(y\), the simulator produces a perturbed value \(\tilde{y}\) using one of two Gaussian noise models:

Additive noise provides an i.i.d. first-order approximation of effects such as IR-drop or thermal variation, while multiplicative noise captures proportional gain variation. Both models reflect common sources of uncertainty in analog memory arrays, and distributed high-dimensional embeddings tend to preserve class separability under such perturbations.

Quantization is modeled as uniform \(b\)-bit rounding that mimics the behavior of ADCs operating at different resolutions. Rather than selecting an arbitrary scale, the simulator learns a realistic quantization step size from the distribution of training projections at 8 bits and then coarsens it for lower precisions. After the classifier is trained, we compute the matrix of training projections

and estimate its spread. With a global standard deviation \(\sigma\), we define the 8-bit quantization range

For a target bit-depth \(b \in \{3,4,5,6,8\}\), the step size is coarsened as

and quantization is applied directly to the real-valued projection:

When per-dimension quantization is enabled, \(\sigma\), \(\text{range}_8\), and \(\Delta_8\) become vectors over dimensions, but the above relationships hold elementwise. Importantly, the quantization scale is learned once at 8 bits from training data and reused across all noise levels and bit-depths, ensuring consistent comparison across precision settings.

Bit-Depth and Hardware Interpretation¶

The parameter \(b\) represents the effective ADC resolution used to digitize analog MAC outputs in a CiM array. Current CiM prototypes typically operate at 6–8 bits to balance accuracy and converter power, while aggressive designs explore 3–5 bits to further reduce energy. In our simulator, we sweep \(b \in \{3,4,5,6,8\}\) to cover both conventional and aggressively quantized regimes.

Lowering \(b\) decreases precision but exponentially reduces converter energy, which we model using the common approximation \(E_{\text{ADC}}(b) \propto 2^{b}\). By combining this scaling with the HDC-style classification pipeline, the simulator explicitly models the trade-off between accuracy degradation and estimated energy savings as a function of ADC bit-depth.

Energy Model¶

To connect algorithmic precision to hardware cost, we estimate per-sample inference energy as

where \(N_{\text{MAC}} = D(F + C)\) covers both the encoding and similarity computations, and \(N_{\text{ADC}}\) represents the number of analog-to-digital conversions per inference. In our implementation, we conservatively assume one ADC conversion per projected dimension, so \(N_{\text{ADC}} = D\). Our energy model accounts only for the CiM inference kernel (in-array MACs plus ADCs). Feature extraction via PCA is treated as a fixed digital pre-processing step and is not included in the energy accounting, as it does not depend on ADC bit-depth and would only shift energy curves vertically.

The energy values are parameterized by two knobs: the per-MAC energy \(E_{\text{MAC}}\) and the per-conversion energy of an 8-bit ADC, \(E_{\text{ADC}}(8)\). By default, we use \(E_{\text{MAC}} = 0.5\) pJ and \(E_{\text{ADC}}(8) = 10\) pJ, consistent with recent device-level measurements39. The ADC energy at bit-depth \(b\) is modeled using the common scaling law

which reflects the exponential dependence of converter energy on resolution. This default regime yields a balanced mix in which both MAC and ADC costs contribute to the total energy.

To probe more extreme hardware scenarios, the simulator also supports alternative regimes in which either the memory array or the converters dominate the energy budget. In particular, for the ADC-dominated regime used in our MNIST experiments, we set \(E_{\text{MAC}} = 0.2\) pJ and \(E_{\text{ADC}}(8) = 40\) pJ, pushing the system into a converter-heavy operating point. This configuration emphasizes the impact of reducing ADC bit-depth on total energy and is the one used to produce the substantial energy reductions (approximately \(50-55\%\)) reported in the evaluation.

Implementation and Evolution¶

The simulator is implemented in Python with NumPy for reproducibility and accessibility across disciplines. This choice reflects a deliberate design philosophy: to make the code usable both by hardware engineers interested in analog modeling and by computer scientists working on algorithmic robustness. Over the course of the project, the implementation evolved through a series of versions:

- v1.1: Implemented baseline HDC encoding and a simple per-sample quantization model without train-learned scaling.

- v1.2: Introduced train-learned global scaling to capture realistic ADC behavior, learning an 8-bit range from training projections and reusing it across bit-depths.

- v1.3: Added a parametric energy model linking ADC bit-depth to estimated per-inference energy, enabling energy-accuracy trade-off analysis.

- v1.4: Integrated unified sweeps across noise and precision levels, multiple datasets (synthetic and

digits), and reproducible plotting for systematic evaluation. - v1.5: Extended the simulator to the 10-class MNIST benchmark via Principal Component Analysis (PCA)-based dimensionality reduction, and added optional per-dimension quantization to better match dimension-wise statistics of high-dimensional projections.

- v1.6: Introduced multi-seed and multi-projection averaging for each \((\sigma, b)\) point, as well as configurable energy regimes (default, ADC-dominated, MAC-dominated). This version also added command-line controls for noise type, dataset, projection dimensionality, and output ranges.

- v1.7: Added a lightweight gradient-trained HDC-style classifier inspired by learned distributed codes8. This version learns both the projection matrix and class vectors via stochastic gradient descent, improving MNIST baseline accuracy to above \(90\%\) and enabling direct comparison of precision scaling in both classical and learned hyperdimensional models. Version 1.7 is the basis for the accuracy and energy results reported in this paper.

A key design decision is the use of pure NumPy with explicit gradient formulas rather than an autograd framework such as PyTorch or JAX. This keeps the simulator compact, transparent, and self-contained, making it easier to reason about the interaction between analog noise, quantization, and hyperdimensional inference. While autograd libraries remain natural options for more complex future models, they introduce additional dependencies and a degree of black-box abstraction that runs counter to the simulator’s goals.

The simulator is also designed for extensibility. Future iterations could incorporate measured device statistics (e.g., drift or spatially correlated IR-drop), software-level calibration strategies, or in-memory associative queries—deepening the co-design connection between analog hardware behavior and algorithmic robustness.

Evaluation¶

Experimental Setup¶

We evaluate the robustness–efficiency trade-offs of our HDC-on-CiM simulator on the 10-class MNIST benchmark, reduced to \(F=128\) features via PCA. Unless otherwise noted, all experiments use projection dimensionality \(D=1024\) and \(C=10\) classes. The gradient-trained HDC-style classifier is trained once on clean data (without injected noise or quantization), after which we learn an 8-bit quantization scale from the distribution of training projections (with per-dimension statistics enabled). This fixed scale is then reused to evaluate bit-depths \(b \in \{3,4,5,6,8\}\) and noise levels \(\sigma \in [0,0.20]\) sampled in 17 steps.

For each \((\sigma,b)\) configuration, accuracy is averaged across three independent model initializations and ten independent noise realizations. Both additive and multiplicative Gaussian noise are tested. Accuracy and energy results are reported for additive noise under both energy regimes, while multiplicative noise is evaluated in the default regime only due to its minimal impact on accuracy. The primary metrics are classification accuracy and modeled energy per inference.

Additive Noise and Quantization Effects¶

Under additive noise, MNIST accuracy remains remarkably insensitive to both noise amplitude and bit-depth. At \(\sigma = 0\) and 8 bits, the mean accuracy is approximately \(0.9126\). Reducing precision to 3 bits changes accuracy by only a few thousandths, and all intermediate bit-depths (4–6 bits) lie essentially on top of the 8-bit baseline. Even at \(\sigma = 0.20\), accuracies across 3–8 bits remain tightly clustered between roughly \(0.9085\) and \(0.9125\), confirming that additive perturbations have only a limited effect on the classifier’s decision boundaries.

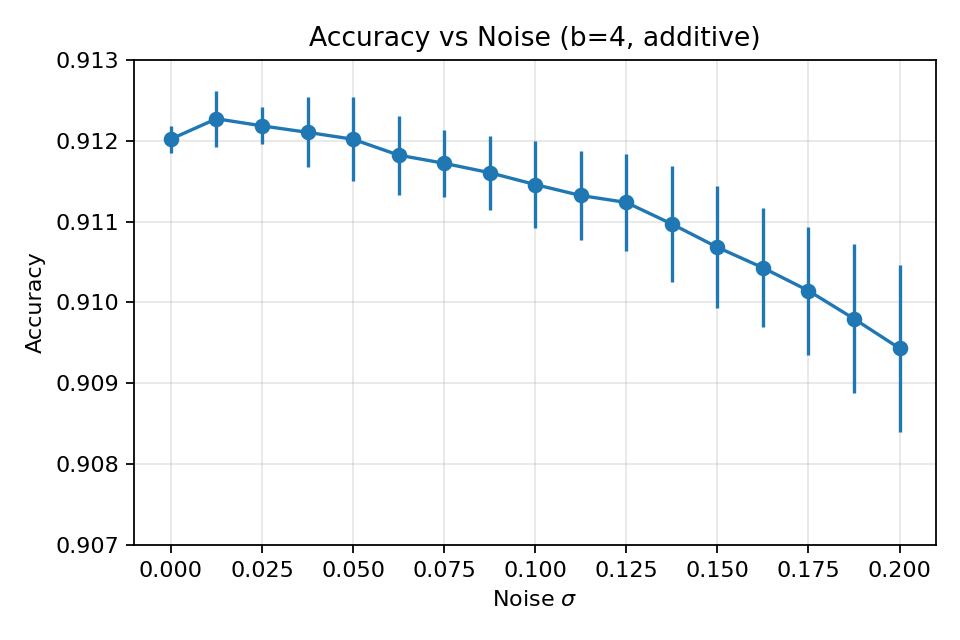

Figure 1 shows accuracy versus additive noise for \(b = 4\). Accuracy declines gently from about \(0.912\) at \(\sigma = 0\) to approximately \(0.909\) at \(\sigma = 0.20\), with error bars reflecting variability across model initializations and noise draws. This confirms that the gradient-trained HDC-style classifier preserves stable performance even under relatively large additive perturbations in the analog domain.

Figure 1. Accuracy varies by only \(\sim 3\times10^{-3}\) as σ increases from 0 to 0.20, illustrating strong robustness to additive perturbations.

Energy–Accuracy Trade-off (Default Regime)¶

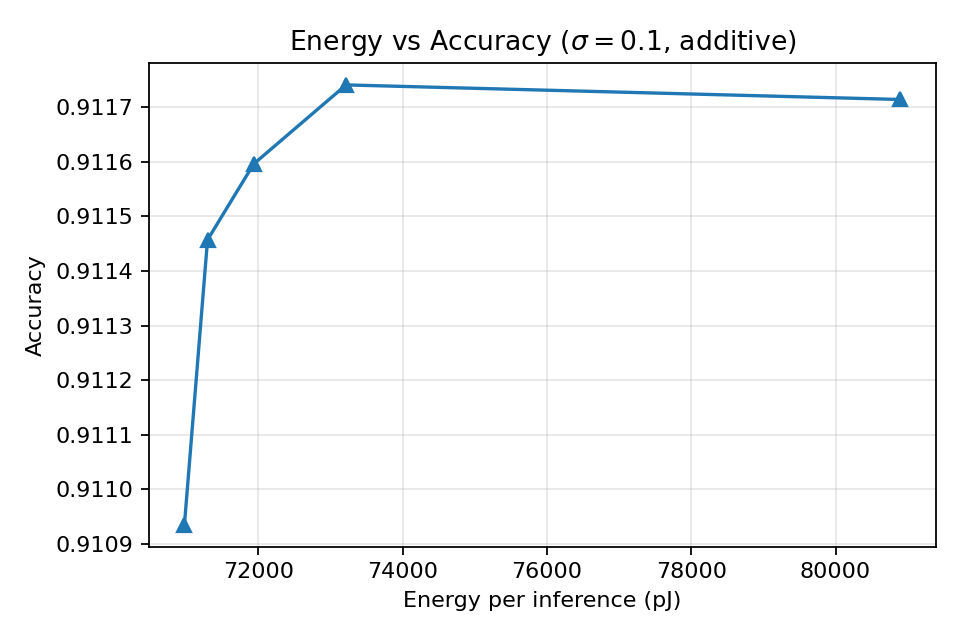

We first combine the accuracy results with the default energy model (\(E_{\mathrm{MAC}} = 0.5\) pJ, \(E_{\mathrm{ADC}}(8) = 10\) pJ). In this balanced regime, ADC energy grows with bit-depth while MAC energy remains fixed. At \(\sigma = 0.10\), moving from 3 to 8 bits increases modeled energy from roughly \(70\,\text{k}\) pJ to about \(81\,\text{k}\) pJ, while accuracy stays effectively constant: all points lie within approximately \(3\times10^{-3}\) of one another. In particular, reducing precision from 8 to 4 bits lowers modeled energy by about \(12\%\) with negligible accuracy change.

Figure 2 shows the resulting energy–accuracy curve. The gradient-trained HDC-style classifier maintains stable accuracy across the entire bit-depth range, confirming that its robustness can be leveraged to reduce ADC precision even in conservative energy settings.

Figure 2. Accuracy varies by only \(\sim 3\times10^{-3}\) as bit-depth increases, illustrating a strong energy–accuracy trade-off plateau.

Energy–Accuracy Trade-off (ADC-Dominated Regime)¶

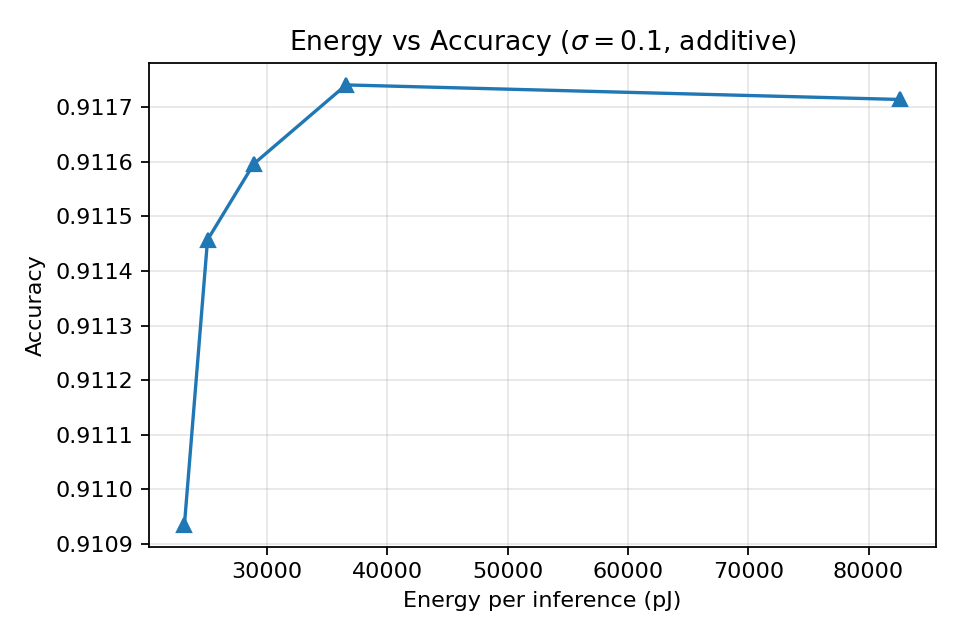

To highlight scenarios in which converter power dominates, we repeat the additive-noise sweep under an ADC-dominated configuration, setting \(E_{\mathrm{MAC}} = 0.2\) pJ and \(E_{\mathrm{ADC}}(8) = 40\) pJ. This shifts the energy budget strongly toward the converters while leaving the classifier unchanged. At \(\sigma = 0.10\), energy drops from roughly \(82\,\text{k}\) pJ at 8 bits to about \(37\,\text{k}\) pJ at 4 bits—a reduction of approximately \(50-55\%\). Accuracy, however, remains within roughly \(3\times10^{-3}\) of the baseline across all bit-depths.

Figure 3 shows the resulting energy–accuracy curve. The gradient-trained HDC-style classifier maintains near-constant accuracy even in this converter-heavy regime, producing a broad Pareto-optimal region at low bit-depths where energy falls sharply while accuracy remains stable.

Figure 3. Energy–accuracy trade-off on MNIST under additive noise (\(\sigma = 0.10\)) in the ADC-dominated regime. Lowering precision from 8 to 4 bits reduces energy by \(\sim50\)–\(55\%\) while accuracy remains within \(\sim 3 \times 10^{-3}\) of the baseline.

Multiplicative Noise¶

Multiplicative noise has an even smaller effect than additive noise. Across all \((\sigma,b)\) combinations, accuracies remain tightly clustered around \(0.912\), with variations on the order of \(10^{-3}\). Because multiplicative perturbations rescale the real-valued projection rather than altering its direction, the relative class scores change very little, leaving the decision boundaries effectively unchanged. We therefore omit multiplicative plots for brevity and use them primarily as a sanity check confirming that additive perturbations—not gain variation—are the dominant accuracy-relevant non-idealities in this model.

Evaluation Methodology¶

Our methodology is designed to isolate intrinsic trends in accuracy, noise tolerance, and precision scaling while suppressing incidental variability. The multi-initialization (three seeds) and multi-noise (ten draws) averaging ensures that each reported accuracy reflects stable behavior rather than idiosyncratic sampling effects. Sweeping the full grid of noise levels and bit-depths allows fine-grained trends to emerge, and per-dimension quantization statistics more faithfully capture the heterogeneous scales of projected dimensions in high-dimensional spaces. Together, these design choices yield smooth accuracy–noise–precision curves and ensure reproducibility.

Discussion and Future Work¶

Overall, our evaluation shows that MNIST accuracy remains effectively invariant across 4–8 ADC bits, and degrades only minimally at 3 bits, even under substantial additive noise, enabling meaningful energy reductions without compromising classification performance. These results quantify how analog noise and ADC precision affect accuracy and energy efficiency for HDC-style inference on CiM hardware. The preceding experiments provide a clear and reproducible map from CiM-level precision parameters to end-to-end classification accuracy, addressing a gap that prior work has explored only qualitatively356. Where prior CiM studies typically compare analog-in-memory accelerators against digital baselines, our work instead focuses on intra-CiM precision scaling: the \(10-12\%\) energy savings in the default regime and the \(50-55\%\) savings in the ADC-dominated regime are both measured relative to an 8-bit CiM baseline. For comparison, a purely random-projection HDC classifier with prototype bundling achieves only about \(76\%\) accuracy under the same evaluation setup, confirming that lightweight gradient-based training is essential to achieving over \(90\%\) baseline accuracy while preserving robustness to noise and quantization.

Beyond confirming the robustness of distributed hyperdimensional embeddings, these findings highlight a valuable representation-compute interaction: the high-dimensional real-valued embeddings produced by the gradient-trained model absorb analog variation, enabling CiM hardware to operate reliably at reduced precision. In this view, converter resolution---traditionally fixed at design time---can be treated as a tunable resource. A CiM compiler or runtime controller could dynamically adjust ADC bit-depth in response to workload characteristics, quality-of-service targets, or energy budgets, exploiting the broad plateau of stable accuracy revealed by our experiments. Such dynamic precision scaling aligns with emerging directions in adaptive hardware--software co-design for sustainable machine learning, where robustness at the algorithmic layer enables flexibility and efficiency at the hardware layer.

Despite these promising outcomes, several limitations constrain the present simulator. The noise models capture independent Gaussian perturbations but do not yet incorporate spatially correlated effects such as row-dependent IR-drop, device mismatch patterns, or long-term drift common in resistive memory technologies. The energy model, while calibrated to realistic orders of magnitude, remains parametric rather than derived from silicon measurements. Although MNIST provides a more informative benchmark than earlier synthetic or low-dimensional datasets, the evaluation does not yet cover higher-resolution image domains, temporal data, or tasks with more complex feature distributions. These simplifications were deliberate to preserve interpretability and isolate first-order trends, but they leave open important avenues for increasing model fidelity.

Future work will therefore extend the simulator along several complementary directions. First, device-aware modeling: incorporating empirical measurements of analog variability, retention loss, converter asymmetry, and spatially structured noise would enable more realistic mappings from circuit non-idealities to algorithmic accuracy. Second, system-level co-design: coupling the simulator with an analog-aware compiler or scheduling system would allow end-to-end exploration of precision scaling policies, ADC sharing strategies across CiM tiles, and workload-dependent adaptations to energy constraints. Third, architectural extensions: simulating associative memory operations, in-memory similarity search, or hybrid analog--digital pipelines would further illuminate how hyperdimensional representations interact with emerging CiM architectures and could remove the need for digitization at intermediate stages. Together, these efforts will refine both the accuracy and applicability of the simulator, evolving it from a proof-of-concept study into a practical design tool for energy-efficient analog computing.

Ultimately, the intersection of HDC-style inference and CiM hardware is not merely an exercise in modeling precision and noise: it represents an opportunity to align computational abstractions with physical constraints. By quantifying how algorithmic tolerance to analog noise and reduced precision translates into tangible energy savings, this work takes an early step toward a unified framework in which analog efficiency and machine learning robustness co-evolve. Such alignment will be central to scaling intelligent computation sustainably in the decades ahead.

References¶

-

Shafiee, A., Nag, A., Muralimanohar, N., Balasubramonian, R., Strachan, J. P., Hu, M., Williams, R. S., & Srikumar, V. (2016). ISAAC: A convolutional neural network accelerator with in-situ analog arithmetic in crossbars. ISCA, 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3007787.3001139 ↩↩

-

Ankit, A., El Hajj, I., Chalamalasetti, S. R., Ndu, G., Foltin, M., Williams, R. S., Faraboschi, P., Hwu, W.-M. W., Strachan, J. P., Roy, K., & Milojicic, D. S. (2019). PUMA: A programmable ultra-efficient memristor-based accelerator for machine learning inference. ASPLOS, 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1145/3297858.3304049 ↩↩

-

Haensch, W., Raghunathan, A., Roy, K., Chakrabarti, B., Phatak, C. M., Wang, C.-C., & Guha, S. (2023). Compute-in-memory with non-volatile elements for neural networks: A review from a co-design perspective. Advanced Materials, 35(37), e2204944. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202204944 ↩↩↩↩

-

Xu, J., Liu, H., Duan, Z., Liao, X., Jin, H., Yang, X., Li, H., Liu, C., Mao, F., & Zhang, Y. (2024). ReHarvest: An ADC resource-harvesting crossbar architecture for ReRAM-based DNN accelerators. ACM Transactions on Architecture and Code Optimization (TACO), 21(3), Article 63, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3659208 ↩↩

-

Kleyko, D., Davies, M., Frady, E. P., Kanerva, P., Kent, S. J., Olshausen, B. A., Osipov, E., Rabaey, J. M., Rachkovskij, D. A., Rahimi, A., & Sommer, F. T. (2022). Vector symbolic architectures as a computing framework for emerging hardware. Proceedings of the IEEE, 110(10), 1538–1571. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2022.3209104 ↩↩↩

-

Karunaratne, G., Le Gallo, M., Cherubini, G., Benini, L., Rahimi, A., & Sebastian, A. (2020). In-memory hyperdimensional computing. Nature Electronics, 3, 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-0410-3 ↩↩↩

-

Kleyko, D., Rachkovskij, D. A., Osipov, E., & Rahimi, A. (2023). A survey on hyperdimensional computing aka vector symbolic architectures, part II: Applications, cognitive models, and challenges. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(9), Article 175, 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1145/3558000 ↩

-

Pu (Luke) Yi, Yifan Yang, Chae Young Lee, and Sara Achour. Early Termination for Hyperdimensional Computing Using Inferential Statistics. Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS ’25), ACM, 2025, pp. 342–360. https://doi.org/10.1145/3669940.3707254 ↩↩↩

-

Soliman, T., Chatterjee, S., Laleni, N., Müller, F., Kirchner, T., Wehn, N., Kämpfe, T., Chauhan, Y. S., & Amrouch, H. (2023). First demonstration of in-memory computing crossbar using multi-level cell FeFET. Nature Communications, 14, 6348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42110-y ↩